This father-son trip requires more than a Rambler

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR: I recently collaborated on a series of blogs with my son Jake Potter for HERstory, a digital magazine aimed at women. The blogs offer, from a male perspective, some reflections on a unique though what I view as quite normal father-son relationship. Our story now includes Jake’s son, Landon, who turned 4 in January. Jake and I wrote the series after a recent trip to Florida for music and beach therapy. This was the concluding entry I put together. I want to share it with my friends here at One Place in Jacksonville, where I now serve as a communications consultant. Jake also is in communications, working at a major airport in the Raleigh area. Fathers play such a critical role in the partnerships for children we promote at One Place; to me, a dad’s positive presence hinges on sticking around to have meaning and influence in his children’s lives. (All four blogs in the series can be found at https://jsg-associates.com/herstory-blog) — Elliott Potter

I wonder if my father ever took stock of his life and asked himself, “What kind of dad have I been to my son?” I wonder if that is a question to which he ever gave much thought; if he did, what was his answer?

Other than my conception sometime in September 1955, Charles Jesse Potter barely had a role in my existence. If we ever slept under the same roof, I was too young to know about it.

Charlie was a sharp dresser, to the point of wearing suits even in casual situations, but that could have been cover for his shortcomings. In the South, we say if you can’t fix it, chrome it. My father always struck me as a braggart, a bit of a legend in his own mind.

Perhaps Charlie believed he met his paternal obligation when he came to my high school years down the road and tried to unload his Rambler station wagon on me. Though I already had a better car and turned his offer down, for that reason and others, the Rambler likely represented a more materialistic gift than he ever received from his dad. (That’s merely a guess, by the way.) For Charlie, maybe the offer of a free car to a son turning 16 checked an important box for being a good father; I just didn’t see things that way.

So, what does that say about me? What kind of son was I?

I never gave Charlie much of a chance to make amends for his absence from my life. I didn’t give him room to explain. I never heard his reason for only showing up when I was riding to church on Sunday mornings and caught a passing glimpse of him while looking out a car window. There he was, standing on a sidewalk in a rundown section of James Street in downtown Goldsboro, N.C., still drunk from the night before.

On the three or four times later in life when we did talk, he only seemed interested in shifting blame for our disconnect on everyone but himself. My youth did not prevent me from seeing right through him; getting an explanation struck me as a lost cause. I guess I was still a little angry.

My bitterness eventually turned to apathy. It became my turn not to give him the time of day. He had lost his chance, and I wasn’t charitable or loving or mature enough to give him a break. Reminds me of that Harry Chapin classic, “Cat’s in the Cradle.”

These days, many years after his death, I would say we failed each other. As a father-son team, we came up empty. At Charlie’s funeral, when one of his brothers asked me what I thought about my father, all I could think of was, “I hope I made him proud.”

In hindsight, that seems awfully weak and self-centered. You need to strive to do more than make your father proud, sons and daughters. You need to be a part of his life. Though we all know reality can present insurmountable obstructions, dig deep and make a thoughtful, prayerful effort.

Maybe something good came out of my shortcomings with Charlie. I feel a lot better about my relationship with my own son, Jake. We both tend to be somewhat reflective and expressive, so Jake and I don’t back away from exploring what has brought us to this point in our lives. (He’s 35, and I am 65.)

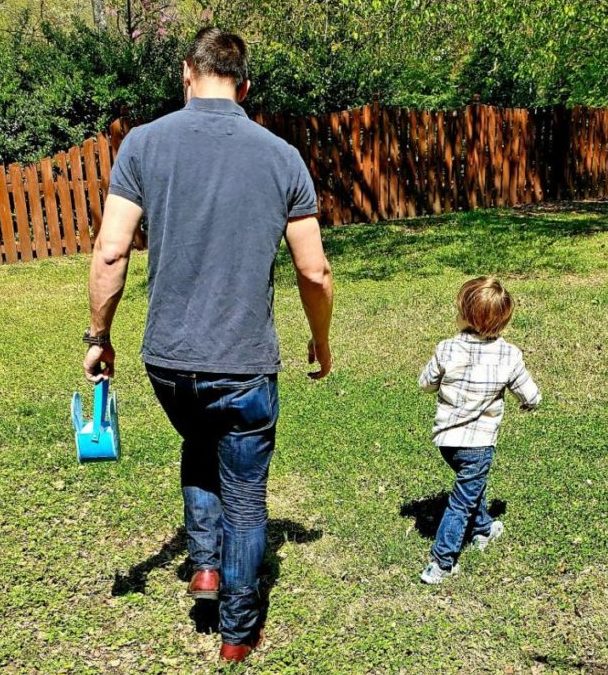

We appreciate the ties that bind: the father-son trips, the music and now my grandson. It’s not a perfect picture, but what we share amounts to more than a Rambler station wagon.

There are plenty of things I could have done differently; for starters, as a divorced dad, I could have done better as a husband to his mom. I wish I had taken Jake to church more often. I prematurely abandoned our golf lessons when chasing down his wild shots produced more tick bites than found balls. It’s a fairly long list.

But I did do one thing that Charlie never did: I hung around. I made critical career and personal decisions with Jake as the primary consideration. A journalist’s life often is nomadic, following a relentless pursuit of job opportunities; I settled. I ended up working and living in a city where I never intended to end up.

I am not complaining. True sacrifice requires giving up something precious for the sake of some other benefit. Children are not a mere benefit; they are a part of life—they give it meaning and continuity. If a parent spends a lot of time lamenting what they might have lost for the sake of their own children, they have it all wrong.

Such profundity brings us full circle in this most recent excursion in the blogosphere—a mid-journey assessment of one father-son relationship. These trips that Jake and I cherish and write about, and this exploration of common ground, are our means of discovery. Other parents and children find their means of discovery using their own maps of experiences and circumstances.

One-on-one travel is time and resources well spent. Finding other horizons opens our eyes to the roads that lie behind us and helps us navigate the landscape still ahead. There is no substitute for shared experiences and time spent together. That was lost on Charlie, but his loss was my lesson.

Jake and I have a distance to go. Our journey now includes my grandson, Landon, and his life journey on the spectrum of autism. It will bring us to new crossroads, where experience serves as a guide but does not determine the destination. As he does so often, Landon has taken our hands and is leading us into new territory.

Like every family living during this pandemic, we are coming off a period of interruption, uncertainty and change. The tools of resilience have been put to a test. In our case, the results have been amazing, but they are by no means complete. Every parent-child relationship is a work in progress.